“Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa”: Traces of an unfinished project

“Personally, a film that isn’t necessary, a film that isn’t deeply rooted in our realities, is a film that doesn’t interest me.” Ahmed Bouanani1

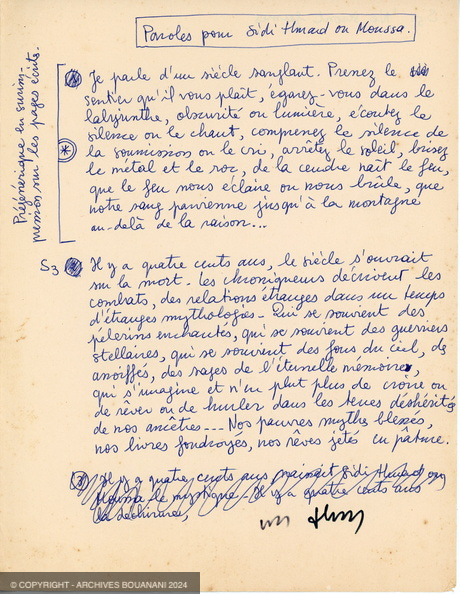

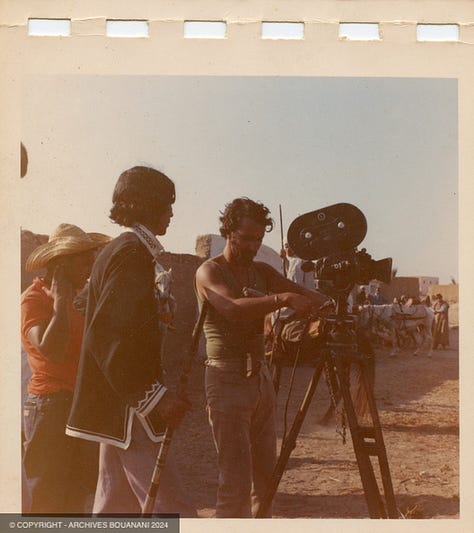

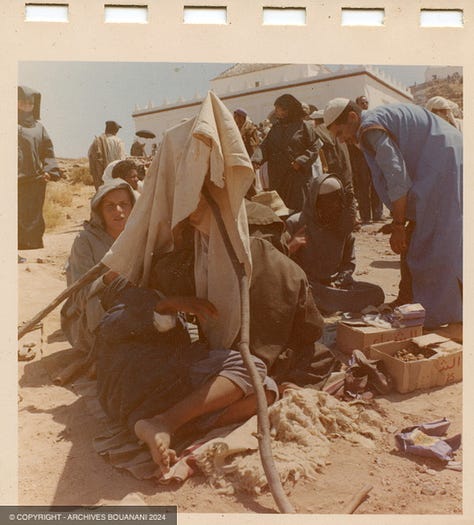

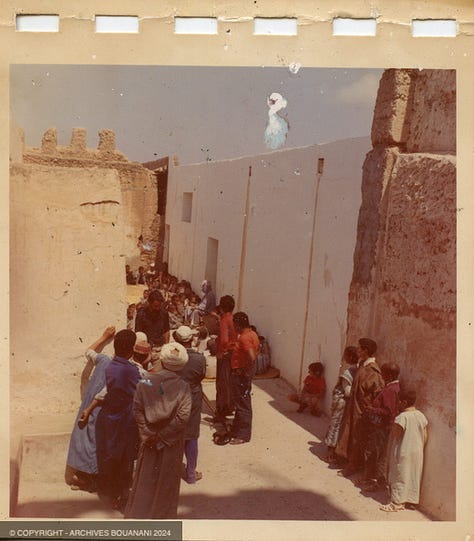

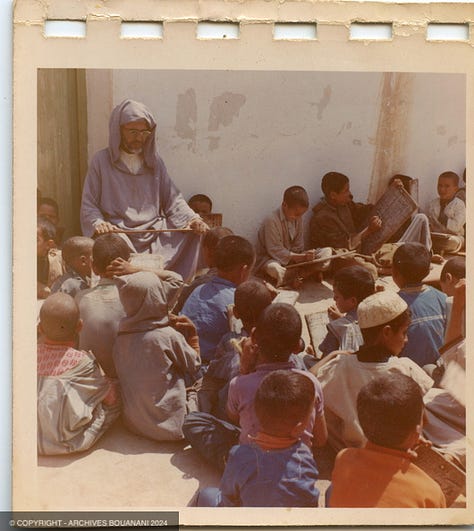

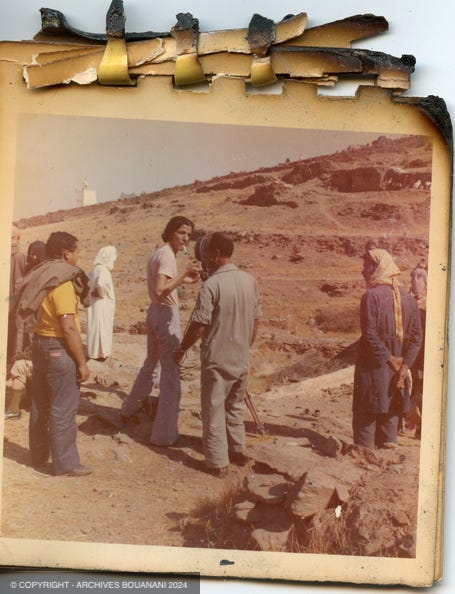

In 1972, Bouanani began work on the film “Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa”. What would have been the filmmaker’s first film in colour would instead remain unfinished due to lack of support from the CCM. A docu-fiction that retraced the trajectory of the long-forgotten 15th century spiritual master and Sufi poet who led armies in the war against the Portuguese colonization of the Moroccan coast. Following the liberation of the territories in question, Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa refused to hold any form of power, returning to his sanctuary and pursuing his studies, teaching, and contemplation.

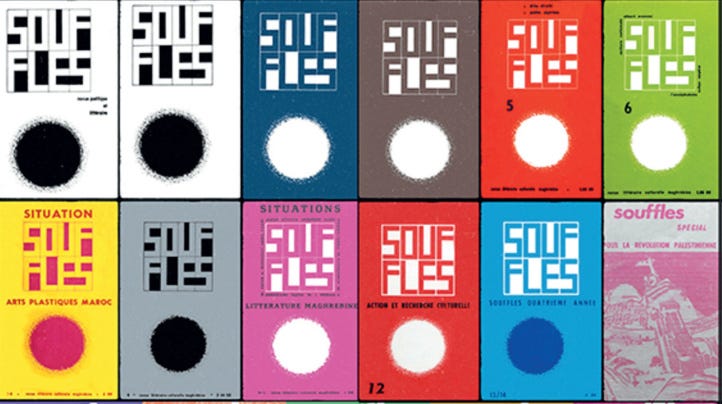

Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa is widely associated with the tradition of acrobats and wandering singers and storytellers who formed part of the popular resistance to colonialism in Morocco. In the 3rd issue of Moroccan socio-political journal Souffles/Anfās/أنفاس published in 1966, Bouanani penned a passionate and comprehensive study of Amazigh Moroccan oral literature.

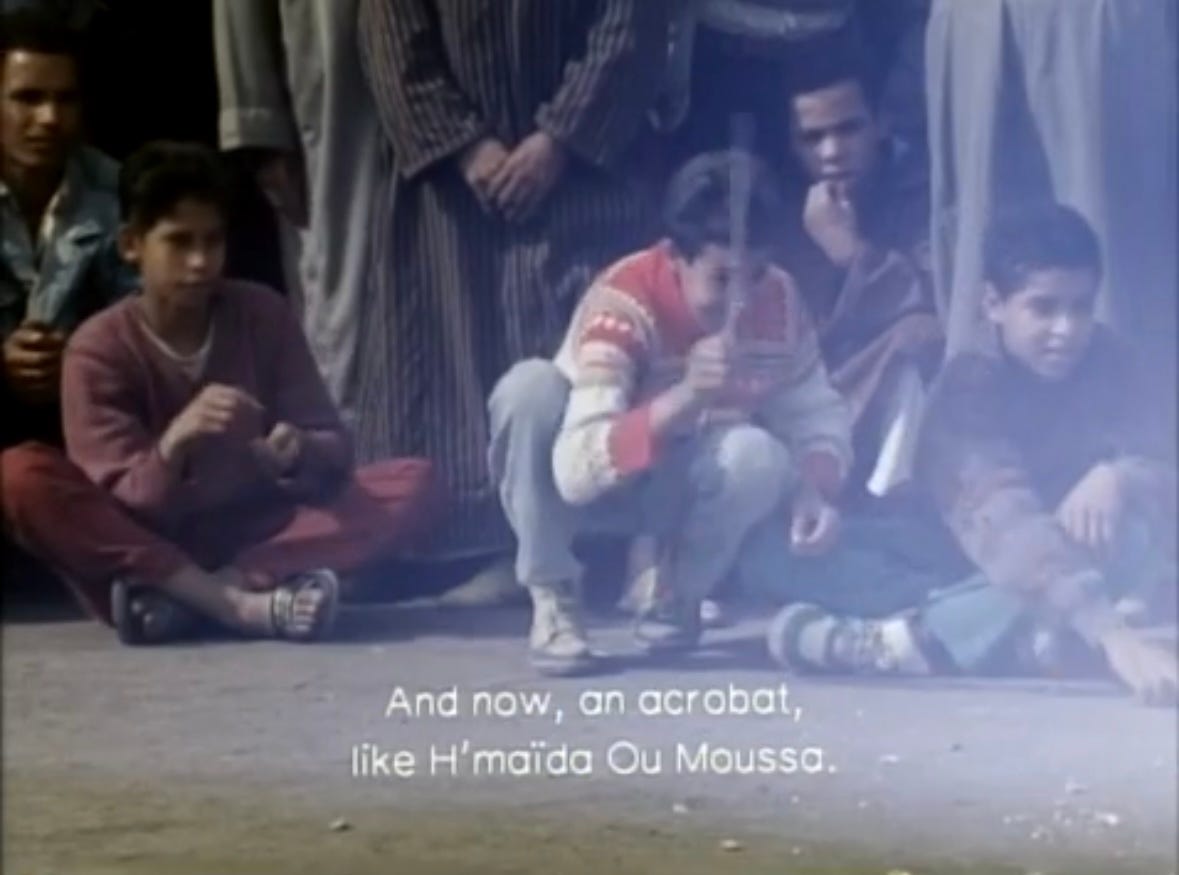

In the old days, itinerant singers such as the acrobats of Ouled Hmad ou Moussa and his storytellers would crisscross the whole country. They were especially numerous in the Middle Atlas range and even more so in the Sous. Their orchestras were composed of four players: the amghar or imdiazen, chief of the troupe; the bou ghanim or flute player, dressed in a colorful ensemble; and two tambourinists in accompaniment. In the Sous itinerant singers occasionally traveled alone or with a child, but more often it was larger troupes that circulated among the towns and villages, improvising poetic songs in their own fashion or chanting the most famous poems of their chief. These itinerant singers earned an important place in the struggle against colonial forces at the beginning of the century as well as under the protectorate. “Today,” writes Basset, “it is these troupes, these orchestras in barbaric costume, always on the move from village to village, who spread the most extraordinary sounds among the rebellious regions and agitate for struggle against the French. They are admired and listened to. They are formidable agents of propaganda.”2

Shot (by Mohamed Sekkat) in the southern region of Morocco where the Sufi poet Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa had actually lived, the cast of Bouanani’s film consisted of non-professional actors, selected from the local population.

In a 1974 interview with Nour-Eddine Saïl, Bouanani stated that the film was not interested in simply valourizing the poet’s mystic thought but was rather preoccupied with recreating the grim atmosphere of his century: “These were the times of deep Moroccan tragedy: perpetual struggle against Portuguese and Spanish conquerors, food shortages, epidemics, heavy taxation, confused philosophical thought, and a stifled national economy. From that economic and social misery, and from that misery of thought, the maraboutic movement was born. Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa was one of the great marabouts of Tazerwalt. There’s an immense mythology around him. He was also, and above all, a leader of the peasant resistance against Portuguese invaders. Unfortunately, no written document explaining his political role under the Saadi dynasty exists. For people today, his name is intimately linked to acrobats. Nothing could be more false.”3

Additionally, Bouanani was attracted to the project since it mirrored the state of affairs of 70s Morocco, a country still alienated by colonialism and its corollary perversion of certain customs and traditions: “The film opens with a coastal village massacre and then gets lost in the maze of a crazy mythology of despair. We’re living today in a similar state of great distress, and it’s not a coincidence that we’ve been witness for some time to a renaissance of Sufi brotherhoods…. Even today in so-called popular music, the lyrics are defeatist. The call to resignation or for patience has never constituted a revolutionary act. The public hears, but doesn’t listen closely enough.”

It only took the CCM’s inner circle one glance at the rushes before rejecting the project wholesale citing the disparity between everyday people taking part in the film and the model of the ideal Moroccan. Despite Bouanani’s many attempts at negotiation and re-editing, the reels were all but abandoned in the laboratory in France where they were supposed to be developed and the film was condemned to non-existence.

As Moroccan filmmaker and one of Bouanani’s many disciples Ali Essafi notes, what had in reality unsettled the censors is Bouanani’s attempt to foreground a heroic figure from the country’s history that had been expunged from the official annals. “Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa” would have been the first film to celebrate Morocco’s Amazigh heritage. By extolling such a figure, the film would have run counter to the official version of history.4

By the 70s, Ahmed Bouanani’s oeuvre and vision had already been the target of several censorship crackdowns which ended with the destruction of some of his work and a banishing to the editing room. Undeterred, it was in that very basement of the CCM that he would hone his editing skills which he later employed as an armour to smuggle his vision under the noses of one-track mind censors.

Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa: Life and legend of the patron saint of poets, musicians…and acrobats

The role of the poet in ancient Moroccan society was considerable. In the first place, he was the chronicler, “the historian” of his tribe. He did not sing merely of his own love affairs and travails but also and above all of the events lived by his tribe or which he experienced as a member of the tribe. During a joust between rival clans, he would be asked to take up the defence of his own. He was respected and venerated as a saint, and his word was heeded, for he was wise and knew the secret of speaking words that went straight to the heart.5

“The old legends tell us much more than the historian, because they transcribe profound realities into symbols.”

As a tribute to the Bouanani-esque approach to historiography, below are fragments of the life and path of Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa gathered from Amazigh oral history and folktales which formed the basis for Bouanani’s original script

Born in Bou Mérouane, into the Idaw Semlal tribe south-east of Agadir. His father was Sidi Massa and his mother Lalla Taounnout. According to his genealogy, he descended from Chérif Sidi Zouzal, the Jazouli, ancestor of the Ida Oultit, who is said to have first settled in Tafraout El Mouloud, where his tomb is found (among the Ida ou Gersmouk).

Legend has it that Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa made many journeys, going as far as Baghdad and as high as Mount Qaf, where popular imagination sees the end of the world. In Baghdad, he spent 40 years heating water for wudu (prayer ablution). After receiving God's divine favour, he decided to renounce the world. He was swept up to heaven and was among the creatures that pull the sun's carriage.

Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa had a turbulent youth. He is said to have toured the country with a troupe of insolent boys, singers, jesters and acrobats. Many accounts of his and his troupe’s naughty antics have been recorded: “At every wedding, he brought his tambourine and carried his flintlock rifle to every communal visit.” However, the origin of his sanctity is said to be a simple act of charity (the tale of the old woman and her basket of figs)

Sidi Hmad u Musa had formed a troupe and became an itinerant acrobat. Once he had come to a place where (he and his friends) met an old lady on the road carrying a basket full of figs. She said to them: ‘‘Please, carry this basket up this hill for me!’’ The acrobats said to Sidi Hmad u Musa: ‘‘Carry this basket up for this old lady, O son!’’ They only wanted to have some fun again. He carried the basket to the top of the hill. This time he remained sensible and pleased the old lady. When he had climbed that hill (for her), the old lady said to him: ‘‘Go, my son, and may God bless you and bless your future actions! ’’ Then he came back (to his companions) and (decided to) devote his life to God.6

A wealth of literature exists on the saint's travels, including motifs like his entry into the Cyclops' lair and his cunning escape. Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa, no dogmatist, believed mysticism couldn't be taught and that God could only be found through inner soul-searching. He used to say, “How many men have died of thirst when the water had reached their beards […] It's because they needed a wise man to bend their heads. Then they would have drunk to quench their thirst.” By this he meant that those who seek knowledge need someone to draw their attention to it in what is closest to them, i.e. within themselves.

In particular, in the “Nozhet El Hadi”7, Al-Ifrani, the historian of the Saadi dynasty, recounts the significant influence of Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa, a contemporary and close friend of Sultan Moulay Abdellah El Ghalib Billah. One can easily envision the crucial role played by a renowned marabout like Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa during such a turbulent period in Moroccan history, when the forces of Christianity were attacking the strongholds of Islam.

In 16th-century Morocco, the nationalism that had long defined Moroccan culture and Islam since the Almohads declined in favour of mystical and spiritual currents. The latter’s proliferation signaled the decline of the political authority's monopoly over religious power and the rise of Zaouïas as legitimate political forces. The practices of Sufi spiritualists and the books of their doctrine spread throughout the country, multiplying religious brotherhoods under the patronage of the great saints of Islam.

After all, faced with the Merinids' failure to put an end to Portuguese encroachments, the tribal world, led by marabouts and Zaouïa chiefs had to spring into action.

It is in this troubled context of Moroccan history that the existence of the great marabout of Tazerwalt is situated.

The Acrobats of Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa or Ouled Ahmed Ou Moussa: A synthesis of martial and spiritual ethos

Similarly, Morocco’s acrobatic tradition, with its martial and spiritual aspects, must be understood within the historical and sociological context of its time. Once a venerated brotherhood of Islamic soldiers, they devoted their talents to fighting the Portuguese invaders.

The Ouled Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa, who invoke the saint of Tazerwalt as their patron saint, are itinerant musicians and singers, dancers, jugglers and above all acrobats who roam the country. They always include 2 or 3 members of the Oulidat (or Abidates) Rma, who today are considered to be jesters and crowd entertainers with a rich and varied farcical repertoire.

The Rmaya originally formed a special caste. The principles of this society, its traditions and a few manuscripts about it were brought back to Morocco in the 16th century by pilgrims from the Sous region. This was at the time of the great struggle against the Portuguese. Within a short space of time, numerous marksmanship societies were organized and the brotherhood expanded. At the siege of Agadir in 1536, they performed prodigious feats of skill: their bullets pierced all the battlements, and they played a major role in the capture of the city. In 1578, at the Battle of the Three Kings, it was their force that prompted the first retreat of Don Sébastien's army.

The services rendered by the Rmaya were so brilliant that the Sultan-Mohamed Ech-Cheikh wanted to give them an organization likely to strengthen their ties. To this end, he chose Sidi Ali Ben Nacer, mokkaddem of the Chadelya and brother of Sidi Mohamed Ben Nacer, founder and grand master of the Naciria, whose mother Zaouïa was at Tamegroute, in the Sous. Sidi Ali Ben Nacer gave a strong religious impetus to the brotherhood. But when he died, the Rmaya soon broke away from the spiritual bond that tied them to the Naciria religious order. The group based in Tazerwalt was the first to regain its autonomy.

In an early research text for his film, Bouanani described Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa’s acrobatic troupe as:

Agile and lively, placed under the protection of Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa, the great saint of Tazerwalt, they form a kind of itinerant brotherhood, whose heart is at the foothills of the Anti-Atlas, and whose influence can be recognized worldwide, as they are recruited in the biggest circuses. True miniatures of the 15th century, in their brightly coloured tunics. Their acrobatic display scaffolds and crumbles like a house of cards, and is relentlessly re-enacted to cries of “YAHIA SIDI AHMED OU MOUSSA/LONG LIVE SIDI AHMED OU MOUSSA”.

Later introduced to Sidi Youssef Ben Ali Sanhaji 8 by Mokadem Mohammed El Oulad Emzin the troupe moved to Marrakech, where its repertoire was enriched by the city’s best Ahwash9 performers. The troupe would soon abandon the coloured tunics in favour for the white farajia (a wide dress tightened at the waist by a brightly-coloured silk cord) and debut choreographies comprising of steps and pirouettes drawn from the dance repertoire of Amizmiz and Imintanoute.

In 1985, another Moroccan filmmaker will pay tribute to Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa and his acrobats. In a rare on-camera appearance, Moumen Smihi portrays a Rifian acrobat who witnesses the French defeat in his film 44 or Tales of the Night. In a cheeky scene, departing French soldiers pass an unnamed figure performing handstands while dressed in the red silk pants and shirt of a Moroccan acrobat in the popular tradition of the Ouled Sidi Ahmed ou Moussa.10 A triumph of indigenous culture and tradition, despite colonial alienation.

Today, the surviving traces left behind by the poet Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa in collective memory are invoked in folk songs and stories and of course his Ouled, the famous acrobats of the Djemâa al-Fna square in Marrakesh.

Archives Bouanani: A labour of love

By the same token, Bouanani’s legacy endures through his disciples or Ouled otherwise known as Archives Bouanani—a collective of family members, researchers, curators, filmmakers and story tellers committed to the tireless, interdisciplinary work vital to preserving our collective memory.

The website offers a wealth of invaluable archival material ranging from photographs taken on set, scans of Moroccan cultural journals and magazines, drawings, letters and testimonials on Moroccan and foreign productions shot in Morocco. These documents were also notably used in the compilation of “La Septième Porte”, Ahmed Bouanani's posthumous work on the history of Moroccan cinema (éditions Kulte).

Video gallery:

1-2: Excerpts from Crossing the Seventh Gate (2017) by Ali Essafi

3-4: Excerpts from Moroccan Chronicles (1999) by Moumen Smihi

5: Excerpt from 44 or Tales of the Night (1985) by Moumen Smihi

Excerpt from an interview by Nour-Eddine Saïl in Maghreb informations (June 29-30, 1974, p. 9). Translated by Joshua Richeson

Ahmed Bouanani, “An Introduction to Popular Moroccan Poetry,” trans. Robyn Creswell, in Souffles-Anfas: A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics, ed. Olivia C. Harrison and Teresa Villa-Ignacio (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016), 46–55

Excerpt from an interview by Nour-Eddine Saïl in Maghreb informations (June 29-30, 1974, p. 9). Translated by Joshua Richeson

Ali Essafi, The “Bouanani-esque” Turn in Moroccan Cinema

Ahmed Bouanani, “An Introduction to Popular Moroccan Poetry,” trans. Robyn Creswell, in Souffles-Anfas: A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics, ed. Olivia C. Harrison and Teresa Villa-Ignacio (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016), 46–55

Harry Stroomer, Tashelhiyt Berber texts from the Ayt Brayyim, Lakhsas and Guedmioua region (South Morocco): A linguistic reanalysis of Récits, contes et légendes berbères en Tachelhiyt by Arsène Roux with an English translation. Berber Studies no. 5. Köln, 2003, pp. 78-79 and pp. 122-123.

Nozhet-el hādi bi akhbar moulouk el-Karn el-Hadi: a chronicle of the Saadian sultans of Morocco

One of the seven patron saints of Marrakech

An Amazigh style of collective performance that contains musical, poetic, choreographic and behavioural elements from southern Morocco. An Ahwash ceremony is typically performed around the time of the harvest and during communal celebrations such as weddings.

Peter Limbrick, Arab Modernism as World Cinema: The Films of Moumen Smihi